Faculty find new ways to teach music during online semester

Heading into the fall semester, the Department of Music faculty all faced one enormous question: how do you teach music online during a pandemic?

The music department’s traditional lecture-style courses adapted smoothly to Zoom, utilizing features like the chat and breakout rooms built into the platform to enable students to ask questions and have small group discussions. But applied courses, such as ensembles and private lessons, face unique challenges due to the nature of their performance-based learning outcomes.

Unfortunately, technology is not yet able to reliably support virtual group rehearsals. Internet speed variances make it impossible for musicians to sync up their playing on a platform like Zoom. To work around these limitations, most ensembles are utilizing recording projects as a means for students to rehearse and produce a finished performance product, like they normally would experience in their end-of-semester concert.

All faculty are working with the limitations that students face based on where they are living and the technology at their disposal, and they each developed approaches to online instruction designed to meet the specific goals of their courses. “We’re all doing it differently. I think there’s probably some things that I’m failing at that others are succeeding at greatly,” said teaching professor Wes Parker, director of jazz studies. “Our students come to us for the experience and for the end result, in more ways than a lot of students, I think. And my goal was for them to walk away from this with something a little more tangible since they don’t get a concert. It felt very important to me to give them something they could be proud of. Something that they’re going to be able to share with family.”

The safety mitigations the department originally invested in to make it possible to teach face-to-face in the fall—such as custom face coverings and bell covers for instrumentalists, new room scheduling protocols to ensure adequate air exchange between occupants, along with many others—enabled all students who live in the area to safely access and use practice rooms, technology and instruments on campus if they wished to do so. Operations coordinator Colin Moore prepared more than a dozen recording and streaming stations to be available for students to work on class projects or to access better audio equipment for their online applied lessons. The department moved quickly to distribute instruments to students who were moving home.

Improvising as only a jazz musician can

For Parker, the shift to teaching online jazz courses involves listening to audio recordings up to 12 hours each day in order to send feedback to the students in his two big bands and three combos. Once the students practice at home and he’s satisfied with the level of their performance, he edits the recordings together into a finished song.

It’s more complicated than it sounds. Like other ensemble directors taking the recording approach this semester, Parker is trying to coach 20 students from the moment they receive the music to the moment they’re ready to perform it without ever being in the room with them. Then he has to make 20 individual parts—recorded on vastly varying equipment—line up together smoothly in the finished product. He starts by making a guide track that includes a metronome and sometimes piano and bass parts. Then the rest of the rhythm section records their parts and he edits them all together. Parker sends that recording to the wind players who record their parts a set number of measures at a time, rather than in one continuous take. He reviews these recordings, asks for changes, and stitches together each section of the track.

Even though the workload is intense and it takes longer to correct small issues that would be resolved quickly in-person, Parker is using technology to make progress with his students. “With the recording software I can show them [on Zoom] where they articulate and if they articulate too early or too late, visually I can show them that, which I think has been impactful.”

Marching band without the marching

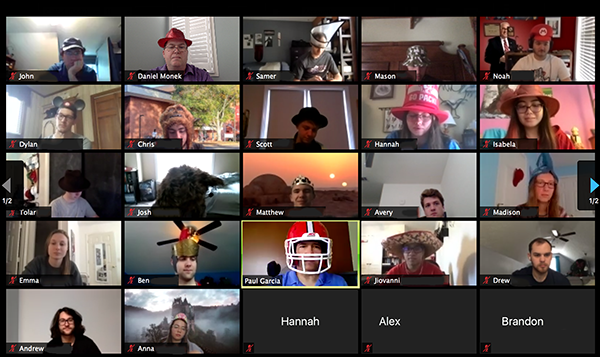

Since live group rehearsal is off the table, teaching professor Paul Garcia, director of bands, is using his virtual class meeting times with the marching band as a chance to check on his 284 students, address any challenges they’re having with the music, and cover topics he wouldn’t necessarily be able to cover during regular practice on the field.

“The marching band class has been the most challenging for me, just because I’m teaching marching band without being able to march,” said Garcia, who also teaches the wind ensemble. “I’ve been working to get a couple of different clinicians to come in [via Zoom]. One of them to do some body work with them, some body awareness exercises, things like that. And then another individual, a phenomenal trumpet player, to talk to them about being a musician and maybe some about leadership as well.”

Garcia is working on several video projects with both the marching band and wind ensemble. He has been intentional about involving students in every step of the project, from planning to performing to editing the final product. That last monumental task belongs to trumpet player Tolar Ray, who has stepped up to edit all of the individual video and audio submissions into finished virtual performances for both ensembles.

Keeping students engaged and managing burn-out are even more challenging with online classes. Garcia tries to address this by continuing to provide leadership opportunities in his ensembles, and conducting the first step of rehearsing a piece on Zoom. He sends the music to his students electronically and then walks through the score with them before they begin rehearsing it on their own, discussing how to approach different sections of the music in order to prepare them for success.

“If they have questions, they can send me a recording of what they’re having an issue with and then I can send them feedback. We talk through everything…Once I go through the music with the students then the section leaders get a sectional and they go over it with their individual sections, answer questions, help individuals that may be having issues. That way when they do go in to make their videos they’ll have a much better time. It’ll be more enjoyable and they’ll be more successful at it.”

Utilizing technology and embracing different learning styles

For associate teaching professor Olga Kleiankina, director of piano studies, her class piano courses (MUS 107 and 207) have a unique advantage in this online semester. Last year, Kleiankina and a team at DELTA developed the Piano+ app, a digital textbook and lesson guide that she had already begun utilizing in her classroom prior to the start of the pandemic. The app makes it easy for her to share music and exercises with her students, and for them to progress at their own pace from home. She also records her class sessions on Zoom so students can revisit them at any time while practicing.

In developing the app, Kleiankina had already begun thinking seriously about how people learn, how the ways we learn are changing, and how she could support those differences in learning styles in her classes. Now she’s seeing that evolution and those distinctions playing out live in front of her. “I noticed that, for example, some students have not attended the course [live on Zoom] for various reasons and they still submitted good playing in their homework submissions. They still did it,” she said. “Some people learn better when they are given resources and they take time to figure it out, because it’s a stressful situation when you have to learn [a piece of music or technique] now in two minutes and then I’m going to ask you to play it. This doesn’t work for everyone. So I’m learning that people have different ways of learning and this online learning is opening new possibilities for us to teach and for students to learn.”

The department moved quickly to make sure students who did not own keyboards could borrow one to take home with them, and Kleiankina determined what equipment she would need in order to successfully teach piano lessons from home. Her setup now includes microphones (both a clip-on lavalier microphone that she wears so students can hear her, and a microphone on a tripod that she can put close to the piano), a webcam on a tripod with an extendable arm, her computer and an iPad. This allows students on Zoom to get a closer look at what she’s doing with her hands as she plays, and she can annotate directly on the sheet music using the iPad and share it with her students.

“Sometimes I can even show things that are closer than you can see in real life. I can lower the camera and really, really show how the fingers are operating, how things are moving, and what I’m doing with my hands. I think people appreciate this aspect of this,” she said. “But of course, for many of them the personal connection was more present when we met in person, so this is something that I feel sorry about.”

She has found that maintaining that personal connection, particularly with the piano performance minors who she both teaches and advises, is the most difficult aspect of this semester. “We’re still learning how to do things, but I think we’re doing okay in terms of making this experience as good as possible for the students…we’re doing our best to stay connected with our students, and that’s meaningful.”

Finding the silver lining

For Kleiankina, one encouraging takeaway has been seeing the determination of her students to continue with music and how much it means to them. “Why do they want to play piano when life is ending? It’s a pandemic, take a break, right? And they’re still interested, so that means something,” she said. “That means it’s a very important thing for their life, for their identity, for their mental health. It’s an indicator that people need arts, people need music when things are very, very difficult. They need it.”

The numbers support Kleiankina’s thinking; students enrolled in music courses in record numbers this fall. While there are challenges and frustrations in teaching these courses online, students are still learning, playing music and making progress. The teaching methods look different, but the learning outcomes are still being met. And along the way, faculty are finding new approaches that they like and plan to keep using.

“The ways that we’ve had to adapt to make this work are going to be techniques that will be helpful for us when we’re back in-person,” said Parker. “I’m more intimately aware of my students’ abilities as musicians than I’ve ever been in my career because I listen to their recordings 12 hours a day. I’ve gotten to a point where in an email I can say, ‘Hey you’re doing this, this, this, and this,’ and, again, nowhere near as effectively as being face to face, but I know exactly what my students can do so much more than before. I’m going to maintain a healthy portion of having them submit recordings…And now, knowing how good of a job we can do of recording tunes from a distance, I don’t ever want to get through a semester without giving them a recording experience at least once or twice a semester.”

Most applied music faculty will be relieved to get back to in-person classes when it’s safe to do so, but the experience of adapting to teach music online may inspire more new methodologies that better support student learning and performance. These innovations will make the department stronger coming out of the pandemic.

To experience some of the music made by our students while learning remotely, visit our YouTube channel and our Soundcloud page.

- Categories: